| HOME | PRESENTACIÓN | ¿FILMAR LA HISTORIA? | DIRECCIÓN-REDACCIÓN | NÚMEROS PUBLICADOS | NORMAS DE PUBLICACIÓN | CONTACTOS | ENLACES |

|

NEO-NAZI SKINHEADS’ DEPICTION La representación de los cabezas-rapada Grad. Eva Gómez Fernández

Recibido el 20 de Noviembre de 2024

Abstract. The article explores the depiction of the neo-Nazi skinhead movement in cinema through nine films spanning the 1980s to the early 21st century. It identifies three central themes: nativism, toxic masculinity, and anti-communist music, emphasizing how these elements perpetuate heteropatriarchal structures across generations within this extremist group. Tracing the movement’s evolution, the study highlights its transformation from an interracial subculture in the United Kingdom into a global phenomenon characterized by rigid, neo-Nazi ideology. The films analyzed illustrate how skinheads employ symbols of white supremacy, music as a powerful mobilizing tool, and construct both internal and external enemies, often driven by conspiracy theories and xenophobia. The article delves into the role of toxic masculinity in reinforcing patriarchal hierarchies through physical and symbolic violence. It also examines the exclusion and subjugation of women and sexual minorities, showing how these dynamics reflect deeper social tensions. Music emerges as a critical force, uniting members and serving as an effective means of indoctrination and cultural cohesion within the movement. Resumen. El artículo analiza la representación del movimiento skinhead neonazi en el cine a través de nueve películas producidas entre los años ochenta y la primera década del siglo XXI. Se identifican tres elementos clave en estas representaciones: el nativismo, la masculinidad toxica y la música anticomunista. Estos elementos evidencian la perpetuación de estructuras heteropatriarcales en este colectivo de corte neonazi de forma intergeneracional. La investigación destaca la evolución histórica del movimiento skinhead desde sus orígenes como una subcultura interracial en el Reino Unido hasta convertirse en un fenómeno global de ideología monolítica y neonazi. Las películas analizadas plasman cómo los skinheads utilizan símbolos de supremacía blanca, la música como herramienta de movilización y la construcción de enemigos tanto internos como externos, basados en narrativas de conspiración y xenofobia. Para concluir, se aborda el papel de la masculinidad tóxica en esta subcultura, donde la violencia física y simbólica refuerza jerarquías patriarcales. También se explora cómo las mujeres y las minorías sexuales son excluidas o subyugadas en estos contextos, mientras que la música se posiciona como un medio crucial para la cohesión y adoctrinamiento del grupo.

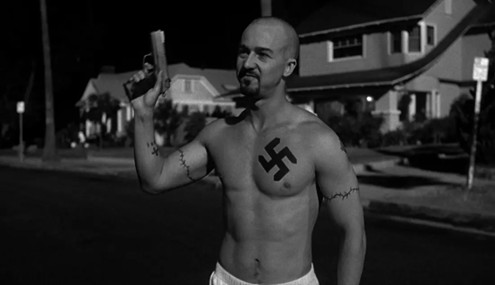

1. Introduction This article explores the core elements of the skinhead phenomenon as portrayed in cinema. To achieve this, we have selected nine films from different eras and countries. Despite the geographical and cultural distinctions of their settings, these films collectively illustrate the ideological and uniformity of the movement. While existing academic research has extensively analyzed the identity of skinhead subcultures, no study has yet examined cinema as a historical testimony that provides a window into this social phenomenon. Films offer a means to develop critical thinking and a deeper understanding of the socio-political realities they portray (Méndez, 2001:23). At the same time, they can reveal the structure of hate-filled ideologies that, due to insufficient awareness, often escape viewers’ attention. While many films aim to expose incitements to hatred targeting specific groups, they frequently fail to provide audiences with the necessary tools to decode such messages. Unlike in other fields of study, there is little precedent for analyzing this topic through the lens of cinema, as films are often undervalued as historical evidence. By examining nine specific films, we aim to identify recurring themes and use them to explore the ideological foundations of the skinhead movement. Like written sources, films may reflect ideological biases. However, the role of the historian is to interpret such materials critically, supported by specialized literature on the topic. Finally, it is essential to recognize the predominance of audiovisual and digital media in modern life. Increasingly, historical research draws on content from social media platforms—a methodology known as netnography (Rodríguez Lajusticia, 2021: 534). This article seeks to offer a new perspective within cultural studies, shedding light on the factors that resonated with a generation of youth marked by heightened politicization, misinformation, anti-establishment sentiment, and economic precarity. The depiction of skinhead youth culture in the selected films demonstrates this vividly, showcasing the ideological mechanisms that perpetuate messages of hate. The aesthetic approach of these films is influenced by the independent cinema movements of the 1960s, such as England’s Free Cinema, New York’s New American Cinema Group, France’s Nouvelle Vague, and Brazil’s Cinema Nôvo. These movements sought to depict the daily lives of marginalized social classes that had previously been overlooked (Gubern, 2014: 352). Of particular significance is Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), an adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel. This film highlights three defining characteristics of the skinhead subculture: violence, antisocial behavior, and anti-establishment attitudes. Its protagonist, Alex DeLarge, like many central figures in these films, follows a narrative arc involving three stages: committing a crime, receiving punishment, and ultimately seeking redemption. Notably, we excluded films such as Pariah (1998) and Diario de un skin (2005) due to their reliance on sensationalism rather than offering a substantive exploration of an international and intergenerational youth phenomenon.

2. When Black Rats Subverted the Principles of May ’68 The term skinhead, derived from the English words skin and head, refers to the distinctive shaved-headed aesthetic adopted by this subculture. Emerging in the United Kingdom during the late 1960s, the skinhead movement arose as a backlash against sweeping sociopolitical and cultural changes, including the second wave of feminism, the advances of the LGBTQ+ rights movement, European social democracy, and the sexual revolution. Predominantly male, anti-establishment, and shaped by economic precarity, this youth culture embodied a fusion of two distinct subcultures (Viñas i Gràcia, 2013: 513–516). On one side were the rude boys, Jamaican immigrants from the Windrush generation who had settled in the UK between 1950 and 1970 as part of post-war labor migration. On the other side were working-class British teenagers, often from disrupted family environments. Both groups shared a rebellious, anti-system ethos shaped by two overlapping economic and identity crises. The politicization of the skinhead movement was accelerated by the National Front’s recognition of music’s mobilizing power. Eddy Morrison, an NF candidate in Leeds, spearheaded efforts to organize rock concerts—a genre intrinsically linked to working-class identity (Forbes and Stampton, 2015: 10). These events proved highly effective due to music fostering social bonds, alleviating stress, and serves as a powerful marker of cultural identity (Borgeson and Valeri, 2018: 90–93). This gave rise to the genre known as Rock Against Communism (RAC), which became an enduring symbol of the movement. By the 1970s, the skinhead subculture adopted a more aggressive and hyper-masculine aesthetic. Shaving their heads and embracing a rugged, working-class wardrobe, they sought to distance themselves from other countercultural movements of the era. This marked the skinheads as the first far-right movement to express a pronounced sense of class consciousness. Interestingly, this class-based identity varied geographically. For example, in Russia, skinheads often came from affluent, well-educated families—a stark contrast to their British counterparts (Yves-Camus and Lebourg, 2020: 127). Despite frequenting neo-Nazi and fascist circles, skinheads were often dismissed by these groups as politically unserious. Far-right ideologues criticized their penchant for substance abuse and football-related hooliganism as detrimental to the far right’s broader parliamentary ambitions (Pecharromán, 2019: 436). Despite these ideological frictions, skinheads appropriated far-right symbols, such as the Celtic cross and the black rat. The black rat became a potent emblem of their rejection of cultural progressivism. Originally used as an insult by leftist students at Assas Law School in France to mock their far-right peers, the rat was reclaimed by neo-fascists as a symbol of defiance against the cultural revolution of May 1968 (Yves-Camus and Lebourg, 2020: 126). This is why, in 1969, filmmaker Barney Platts-Mills, drawing inspiration from the French Nouvelle Vague, released Bronco Bullfrog, a film that captured the nascent characteristics of the skinhead subculture. Rather than analyzing films individually, this study examines recurring themes across cinematic depictions of skinheads to reveal how neo-Nazi ideologies are both reflected and reinforced in these portrayals. Central to this analysis is the construction of the enemy. Skinhead cinema often frames the other as a dual threat. On the one hand, an internal threat where political elites and institutions are portrayed as corrupt and disconnected. On the other hand, external threats where broader forces such as capitalism, communism, globalization, and progressivism are cast as existential dangers. This binary framing—Us versus Them—continues to underpin the hate-filled rhetoric of contemporary far-right movements, making these films a powerful medium for exploring the roots and evolution of extremist ideologies.

3. Arms against the invader (1): A Political Narrative Through Cinema The three central themes in these films are: national identity as a form of nativism, an ideological stance that prioritizes the privileges of natives over immigrants, often fueled by conspiracy theories derived from apocalyptic literature. Toxic masculinity as a defining trait of skinheads. And, lastly, music is a driving force behind social mobilization. 3.1. White Country (2): National Identity

To understand the evolution of this ideology, it’s crucial to acknowledge that the movement spread beyond the UK to other countries like France, where post-decolonization saw a surge of immigrants from former colonies, and the United States during the Cold War. Amid the promise of the American Dream and the Civil Rights Movement, certain factions of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and other fundamentalist religious groups, like the Church of the Creator, began aligning with this new youth identity. This ethnocultural component reshaped the movement’s original interracial myth, giving it a supremacist dimension. This revisionism was further bolstered by three key literary works that, by the late 20th century, helped to spread conspiracy theories. The first, Jean Raspail’s 1973 novel The Camp of the Saints, predicted that the mass influx of immigrants from Africa and Southwest Asia, where Islam was dominant, would cause the collapse of Western civilization. It argued that these immigrants would not assimilate into European culture, thereby leading to the demographic decline of the white, Catholic population. The novel also claimed that immigration would dismantle the welfare state and lead to widespread criminality, including vandalism and the systematic rape of European women (Raspail, 2005:15-19). This narrative helped fuel the rhetoric of France’s National Front, led by Jean-Marie Le Pen, and laid the foundation for right-wing populism in Europe. The novel also became a precursor to later Islamophobic ideologies. In the U.S., white supremacist William Luther Pierce, leader of the National Alliance, wrote The Turner Diaries in 1978 under the pseudonym Andrew Macdonald. This apocalyptic novel predicted a racial war led by militias to eliminate multiculturalism. Pierce argued that feminism, along with the influence of radical feminist movements, had disrupted traditional gender roles and undermined religious values (Pierce, 1978: 93).These works sowed the seeds for a fictional racial war in which skinheads often saw themselves as warriors tasked with eliminating invaders — namely, immigrants. This gave rise to conspiracy theories, including the concept of the Great Replacement, popularized by Renaud Camus, which claimed that the white, Catholic, Christian, and European population would gradually disappear (Zúquete, 2018). This conspiracy laid the foundation for the narrative of white genocide, suggesting that miscegenation, racial integration, and birth control would increase the non-white population. These theories, explored in films like American History X (Kaye, 1998), The Believer (Bean, 2001) and Skinning (Filipovic, 2010) were not isolated. During the 1980s and 1990s, amid the wars in Afghanistan, the Gulf, and Iraq, ultranationalist groups, fueled by memories of the Crusades, viewed Islam as a religion of conquest. As conflicts forced many to flee their countries, seeking refuge in the West, the September 11, 2001, attacks amplified anti-Muslim rhetoric (Traverso, 2019: 89-91). In parallel, the skinhead movement also embraced both antisemitism and anti-Zionism. Antisemitism refers to the hatred of Jews regardless of their location, as seen in The Believer (Bean, 2001) while anti-Zionism rejects the establishment of Israel, viewing it as an oppressive state for Palestinians. Although anti-Zionism is not inherently antisemitic, Michel Wierviorka (2018: 99) notes that it can cross into antisemitism when Jews are universally equated with the Israeli state. In the film Skinning, the protagonist, Michel Downey, distances himself from antisemitism by accepting a Jewish, progressive public defender, suggesting a nuanced stance on the issue. These films often reference the concept of the ZOG (Zionist Occupied Government), a term coined by white supremacist Eric Thompson in 1976 to assert that governments are controlled by Jewish interests and Israeli laws (FBI, 2019: 8). Pierce also contributed to this narrative, claiming that Jews had fabricated a hegemonic story to indoctrinate Americans into their worldview (Pierce, 1978: 73). In American History X (Kaye. 1998), The Believer (Bean, 2001), and Skinning (Filipovic, 2010), references to ZOG are accompanied by violent slogans such as Death to ZOG, Kill ZOG, and Smash ZOG. But these films are not just about Jews. Other minority groups also face racist violence. In Romper Stomper (Wright, 1992) the skinheads aim to create a white ethnostate or ethnocracy, a term Alexandra Mirnn Stein (2019: 51-66) uses to describe a system of government in which one ethnicity, in this case, Caucasian, dominates others. The film primarily focuses on violence against Asian immigrants, but anti-Asian racism itself has a deep history in the United States, particularly around the late 19th century when Chinese immigrants settled in California during the Gold Rush (Berlet and Lyons, 2016: 20-40). This racism, shaped in part by religious differences (Protestantism in English-speaking countries versus Buddhism in China), played a role in the rise of extreme-right movements in Steel Toes (Gow, 2007). In Romper Stomper (Wright, 1992) the violence is mainly directed at Vietnamese communities, driven by religious and anti-communist sentiments. After the Vietnam War (1955-1975), during which Australia supported the U.S. military in countering the Viet Cong, many Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees arrived in Australia between 1976 and 1981 (Phillips and Spinks, 2013: 2-10). While the skinheads’ attacks were directed primarily at Vietnamese immigrants, they embodied a broader anti-Asian sentiment.

A similar pattern can be observed in This is England (Meadows, 2006) where skinheads graffiti phrases like paki bastards and paki fuck off, reflecting the reality of post-colonial Britain, where Pakistan was a British colony from the 18th century until 1947. Many Pakistani immigrants, predominantly Muslim, settled in Britain, opening shops and contributing to the economy. Though the attacks were primarily aimed at Pakistanis, the violence extended to all non-British citizens, as Pakistanis were the most prominent immigrant group in the UK at that time. A comparable situation appears in Skinning (Filipovic2010), a Serbian film, where a Croat-Skinhead protagonist faces hostility based on historical and cultural tensions between Serbs and Croats. Despite both groups being Orthodox Christians, their rivalry stems from the creation of Yugoslavia in 1918 and the ensuing decades of political and territorial conflict. The protagonist, Novica, brutally attacks his maternal cousin after learning that his grandmother was both Jewish and Croatian, illustrating how the past continues to shape ethnic and ideological tensions today.

3.2 Man Against Time (3): Toxic Masculinity For skinheads, the ideal woman was one who embraced domesticity, where inequality was necessary to establish sexual domination and maintain a male hierarchy. Emerging during a time of rapid social change, members of this youth subculture saw themselves as men who had been left behind by society, victimized by a system that had been overtaken by liberal and feminist ideals. Aligned with these views of hegemonic masculinity, which celebrated traditional virility, physical, sexual, and verbal abuse toward women within skinhead circles was not uncommon. To assert their working-class identity, skinheads often adopted behaviors connected to toxic masculinity, such as engaging in fights with rival soccer fans, as seen in Skinning (Filipovic, 2010) and Meantime (Leigh, 1982), consuming alcohol or drugs, and displaying aggression toward women. Many came from dysfunctional family backgrounds where women were subjugated by norms that internalized abusive behaviors, making physical violence, symbolic aggression, and sexual abuse seem normal (Bourdieu, 2016:15-50). Meantime illustrates this dynamic, showing Colin, a vulnerable young man influenced by a skinhead friend, who grew up in a phallocentric household. His father believed that women should stay out of politics, religion, and economics, often legitimizing violence against his wife. Before resorting to violence, skinheads often engaged in erotic games similar to those practiced by officers in the Third Reich. Their working-class appearance was sometimes altered with military-style uniforms, a deliberate aesthetic that played into erotic excitement and symbolized sexual domination (William Reich, 1980: 189-192). This is clearly demonstrated in Skinning (Filipovic, 2010) and Romper Stomper (Wright, 1992), where promiscuity among men is portrayed, with skinheads exploiting young women for sex (Borgeson and Valeri, 2014: 70). However, the reality was more complex: the central character, Hando, developed a toxic attachment to his girlfriend, Gabrielle, subjecting her to psychological and sexual abuse. When she left him for another skinhead who was not a neo-Nazi, Hando sought revenge. While some women were part of the skinhead subculture, they were not necessarily skin girls. In This Is England (Meadows, 2006), for example, some women were involved in antifascist or communist movements, not in the neo-Nazi faction. Furthermore, the skinhead movement, across its various forms, was deeply masculine, characterized by hierarchical, patriarchal behaviors and, in some cases, a phenomenon known as female masculinity, where women adopt traits traditionally associated with hegemonic masculinity without necessarily identifying as lesbians (Borgeson and Valeri, 2014: 67). In Russia 88 (Bordin, 2009), women’s roles were primarily confined to the domestic sphere, and these women experienced more violence than those in other political contexts (Borgeson and Valeri, 2014: 70). The role of homosexuals within this movement is also significant. While designers like Jean Paul Gaultier have used skinhead aesthetics on the runway, the reality within the movement was far less glamorous. Homosexuality was associated with femininity, and same-sex sexual practices were seen as unnatural. Homosexual men were stereotypically associated with traits considered feminine, such as fragility and emotionalism. The rise of the skinhead movement coincided with a time when LGBT+ activists were gaining more freedom to express their sexual identities. However, the movement was notoriously violent toward homosexuals and men they deemed insufficiently masculine. This violence was referred to as queer bashing or fag bashing (Viñas i Grácia, 2013: 26). In Skinning,(Filipovic, 2010) a character named Novica brutally beats his teacher, suspecting him of being gay. Despite the movement’s homophobic undertones, some gay men were drawn to the skinhead aesthetic, which seemed more virile compared to the effeminacy they perceived in other parts of the LGBT+ community. Nonetheless, it was uncommon for homosexual men in the neo-Nazi faction to openly identify as gay. Borgeson and Valeri (2014: 40-51) also point out that, in working-class circles, openly identifying as gay was difficult due to strong societal prejudices, and until 1990, homosexuality was still classified as a mental illness. This complex intersection of toxic masculinity, homophobia, and violence within the skinhead movement reveals the ways in which cultural and social dynamics can shape identity, both collectively and individually. While some sought power and belonging through their aggressive stances against women and homosexuals, it was often rooted in deep insecurity, a desire for control, and a rejection of changing societal norms.

3.3 Blood of our kind (4): Music as a Mobilizer of Youth Much of this music, considered patriotic and nationalist by its creators, was rooted in anti-communist rock, especially after the formation of the British organization Blood and Honour (B&H), which was funded by far-right political groups. This model spread to other countries, including Sweden, Spain, the United States, and France. Despite the movement's loose structure, allowing for autonomous chapters, it sparked the rise of the National Socialist Black Metal (NSBM) subgenre, particularly in Scandinavia (Yves-Camus and Lebourg, 2020: 124-129). In addition to its musical influence, this subculture developed distinctive identity markers, including specific choreographed dance styles. These can be seen in films like American History X (Kaye, 1998), This is England (Meadows, 2006) and Skinning (Filipovic, 2010) These dances included Kicking Knuckles, where individuals struck their knuckles in time with the music; Boot Stomping, where a circle of 10-15 men formed, and the most aggressive would stomp the ground in the center while others rotated around him; Pogo or Moshing, a high-energy, acrobatic style of dancing where individuals purposefully collide with others; and Thrashing or Slam Dancing, which involved shoulder-bumping and forceful movements (Borgeson and Valeri, 2014: 105). These rituals were meant to demonstrate who was the most violent, the most virile, and who could assert dominance within the group. Although this music style remains closely associated with skinhead culture, it has evolved over time. Today, the subgenre known as fashwave—a blend of fascism and vaporwave—has largely replaced the earlier sound. Fashwave combines electronic beats with speeches from dictatorial figures, set against pastel-colored backgrounds like pink and turquoise, with neon lights and imagery of Roman and Greek statues. The genre often includes a retro VHS effect, creating a nostalgic, almost dystopian aesthetic. Fashwave has also given rise to other subgenres, such as Cathwave which incorporates Catholic themes, and Trumpwave, which is infused with Trumpist ideology (Jäger and alii., 2021: 5-14). Music has been a powerful vehicle for shaping and reinforcing the identity of far-right youth movements. Through its aggressive rhythms, populist lyrics, and raw energy in live performances, it continues to serve as a means of mobilization, indoctrination, and cultural cohesion within these subcultures.

4. Final Remarks This article has highlighted the ideological rigidity that characterizes the skinhead movement, which, in many ways, consolidated itself after the 1970s. During this period, the movement reinvented itself by abandoning its interracial origins in favor of a neo-Nazi ideology, influenced by three key writings that are conspiratorial, misogynistic, racist, and violent. This worldview shaped a combative narrative centered on a stark division between us and them, a theme consistently reflected in the films analyzed. The chronological framework used in this study allows us to draw two main conclusions. First, although the skinhead movement initially had an interracial foundation, it has evolved into a highly uniform, monolithic ideology with little variation across different countries. Second, the ideological parasitism evident across the films—spanning approximately three decades—cannot be ignored. This ideological continuity helps explain the recurring themes found in the films, though this should not be taken to mean that their depiction of reality is inaccurate. To sum up, cinema provides a realistic and complex view of the skinhead phenomenon, offering a far more nuanced portrayal than the sensationalized narratives often promoted by the mainstream media.

Notes (1) RAC song by the Spanish band Estirpe Imperial. (2) RAC song by the British band No Remorse. (3) RAC song by the Canadian band RaHoWa, these are the initials letters of Racial Holy War, a concept coined by the founder of the Church of the Creator, Ben Klassen. (4) RAC song by the British band Brutal Attack.

Filmografía PLATTS-MELLS, B., Bronco Bullfrog, United Kingdom, 1969. LEIGH, M., Meantime, United Kingdom, 1982. WRIGHT, G., Romper Stomper, Australia, 1992. KAYE, T., American History X, United States of America, 1998. BEAN, H., The Believer, United States of America, 2001. MEADOWS, S., This is England, United Kingdom, 2006. GOW, D., Steel Toes, Canada,2007. BORDIN, P., Russia 88, Russia, 2009. FILIPOVIC, S., Skinning, Serbia, 2010.

Bibliography BERLET, C., and LYONS, M. N., Right-Wing Populism in America: Too Close for Comfort, The Guilford Press, New York, 2016. BORGESON, K. and VALERI, R. M., Skinhead history, identity, and culture, Routledge, New York 2014. BOURDIEU, P., La dominación masculine, Editorial Anagrama, Barcelona, 2006. FBI (2019). “Anti-Government, Identity Based, and Fringe Political Conspiracy Theories Very Likely Motivate Some Domestic Extremist to Commit Criminal, Sometimes, Violent Activity”. Intelligence Bulletin 1(15). https://www.justsecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/420379775-fbi-conspiracy-theories-domestic-extremism.pdf FIGES, E., Patriarchal attitudes: Women in societies, Persea books, New York, 1986. FIRESTONE, S., The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, London Verso Books, London, 2015. FORBES, R. and STAMPTON, E., The White Nationalist Skinhead Movement: UK & USA, 1979 – 1993, Feral House, Washington, 2015. GIL PECHARROMÁN, J., La estirpe del camaleón: Una historia política de la derecha en España (1937-2004), Editorial Taurus, Barcelona, 2019. GUBERN, R., Historia del cine, Editorial Anagrama, Barcelona, 2014. JÄGER, L. and alii., Fashwave Rechtsextremer Hass in Retro-Optik. De:Hate, 2, Germany, 2021. MÉNDEZ GARRIDO, J. M., Aprendemos a consumir mensajes. Televisión, publicidad, prensa, radio, Grupo Comunicar, Huelva, 2001. MUDDE, C., Populist radical right parties in Europe, Cambridge University Press, 2007. NAGLE, A., Muerte a los normies, Orcinity Press, 2018. PHILLIPS, J. and SPRINKS, H., Boat arrivals in Australia since 1976, Parliament of Australia, Department of Parliamentary Services, 2016. PIERCE, W. L., Los diarios de Turner. Europans, 1978. RASPAIL, J., El desembarco, Ediciones Áltera, 1973. REICH, W., Psicología de las masas del fascismo, Bruguera, Barcelona, 1980. RODRÍGUEZ LAJUSTICIA, F. S., “Juan Sin Tierra, rey de Inglaterra, en el cine”. Vegueta: Anuario de la Facultad de Geografía e Historia 21, 1, (2021), 531-560. SHELHOVTOV, A., “European Far-Right Music and Its Enemies”, in Ruth Wodak, John E. Richardson (eds.) Analyzing Fascist Discourse: European Fascism in Talk and Text, Routledge, London, 2012, 277-296. STERN, A. M., Proud boys and the white ethnoestate: How the alt-right is warping the American imagination, Beacon Press, Boston, 2019. TRAVERSO, E., Las nuevas caras de la derecha: Conversaciones con Régis Meyran, Siglo XXI, Madrid, 2019. VIÑAS i GRÁCIA, C.,"Skinheads" a Espanya: Orígens, implantació i dinàmiques internes (1980-2010), Universitat de Barcelona, 2013. WIERVIORKA, M., El antisemitismo explicado a los jóvenes, Libros del Zorzal, Buenos Aires, 2018. YVES-CAMUS, J. and LEBOURG, N., Las extremas derechas en Europa. Nacionalismo, populismo y xenofobia, Clave Intelectual, Madrid, 2020. ZÚQUETE, J.P., The identitarians: the movement against globalism and Islam in Europe, University of Notre Dame Press, 2018.

ISSN 1988-8848

|